2025 Art Project

2025 Art Project

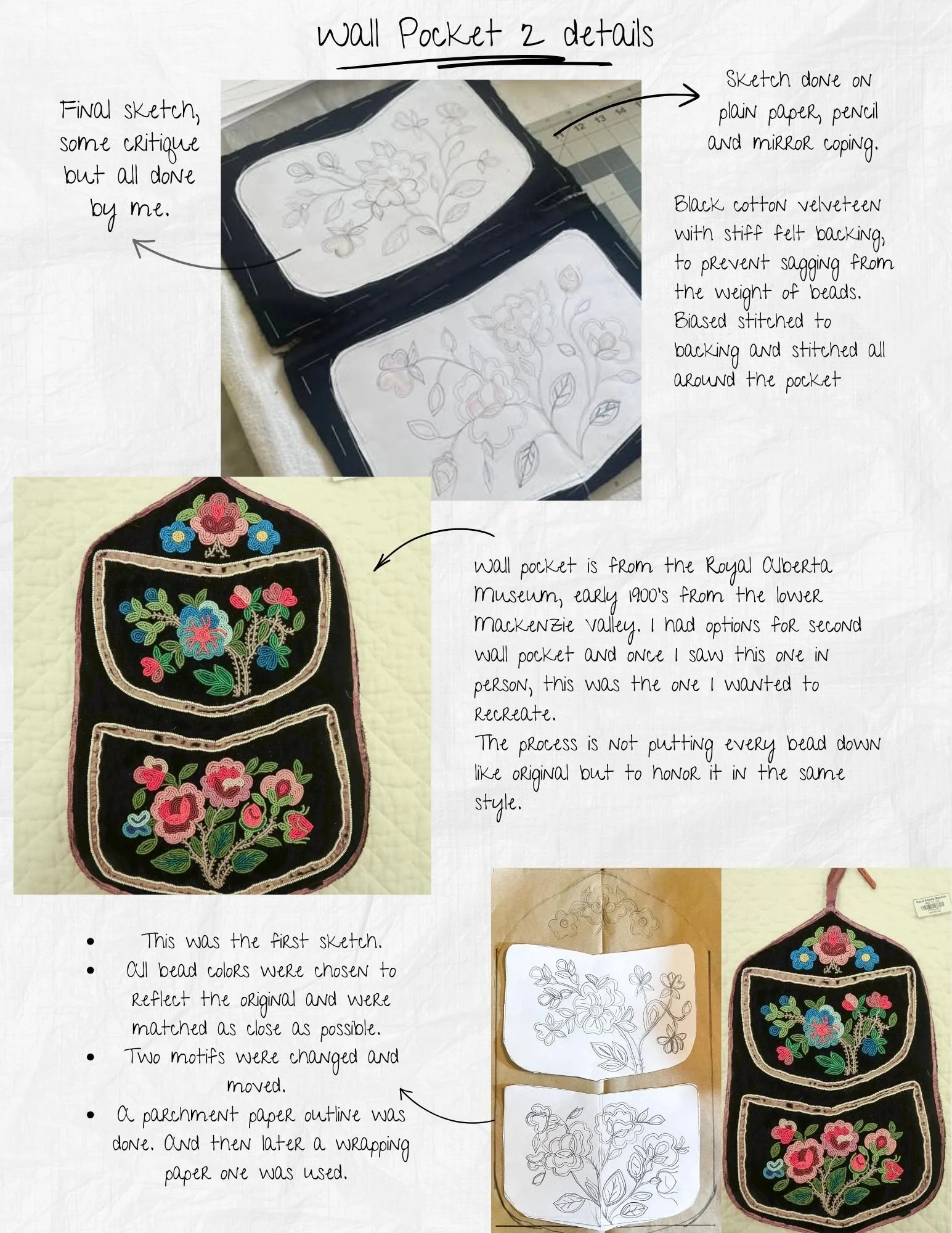

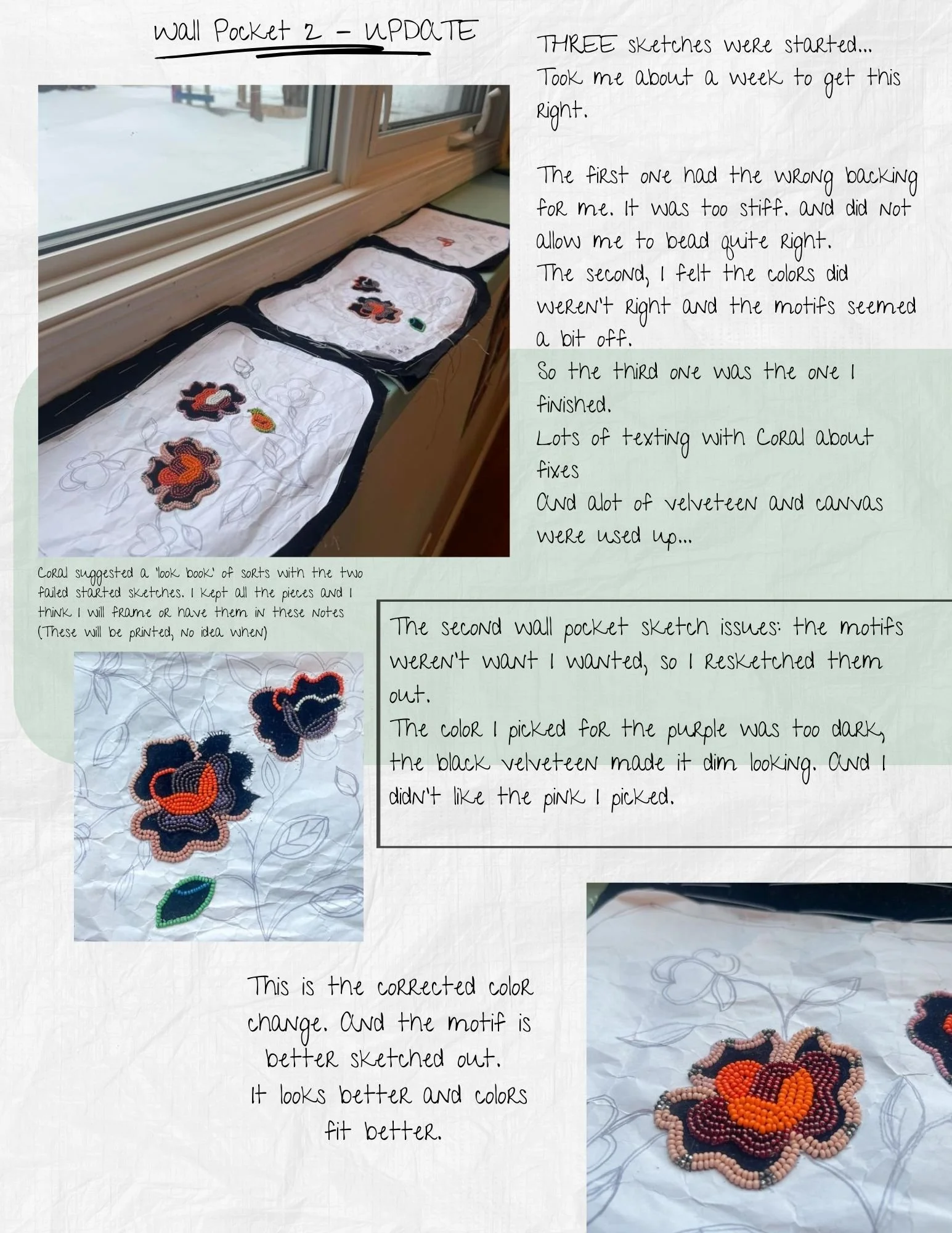

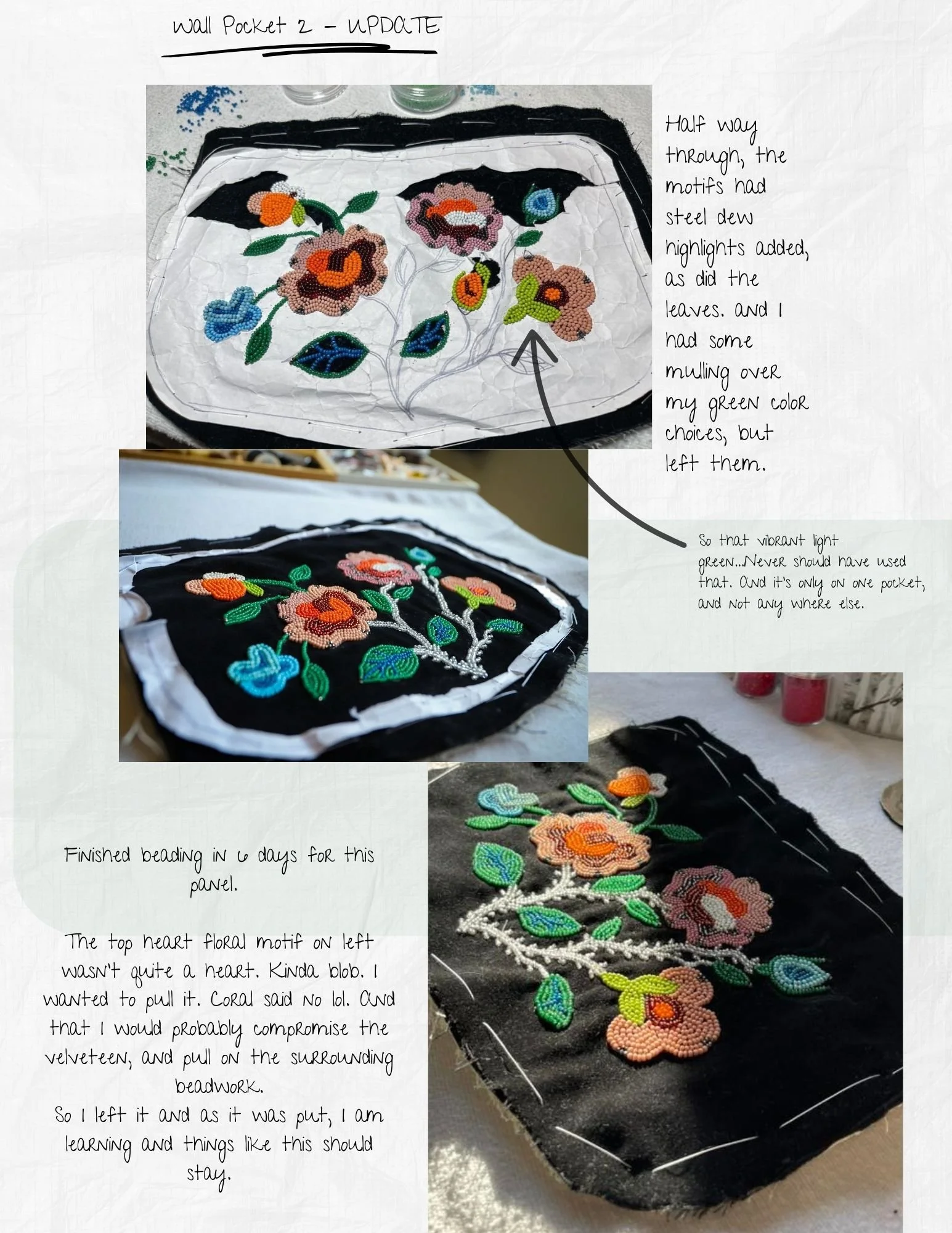

-

In mid 2024, after visiting the Royal Alberta Museum for the second time, I wanted to honor my ancestors work. With the help of my mentor, I knew I wanted to bead and create Dene Wall Pockets. With their help, we wrote an art grant. Requesting the time to make two Gwich’in wall pockets and to research Lower Mackenzie River motifs and styles from the early 1900s.

-

This project stretched 6 months here in early 2025.

Jan-Feb was learning how to make a small pocket.

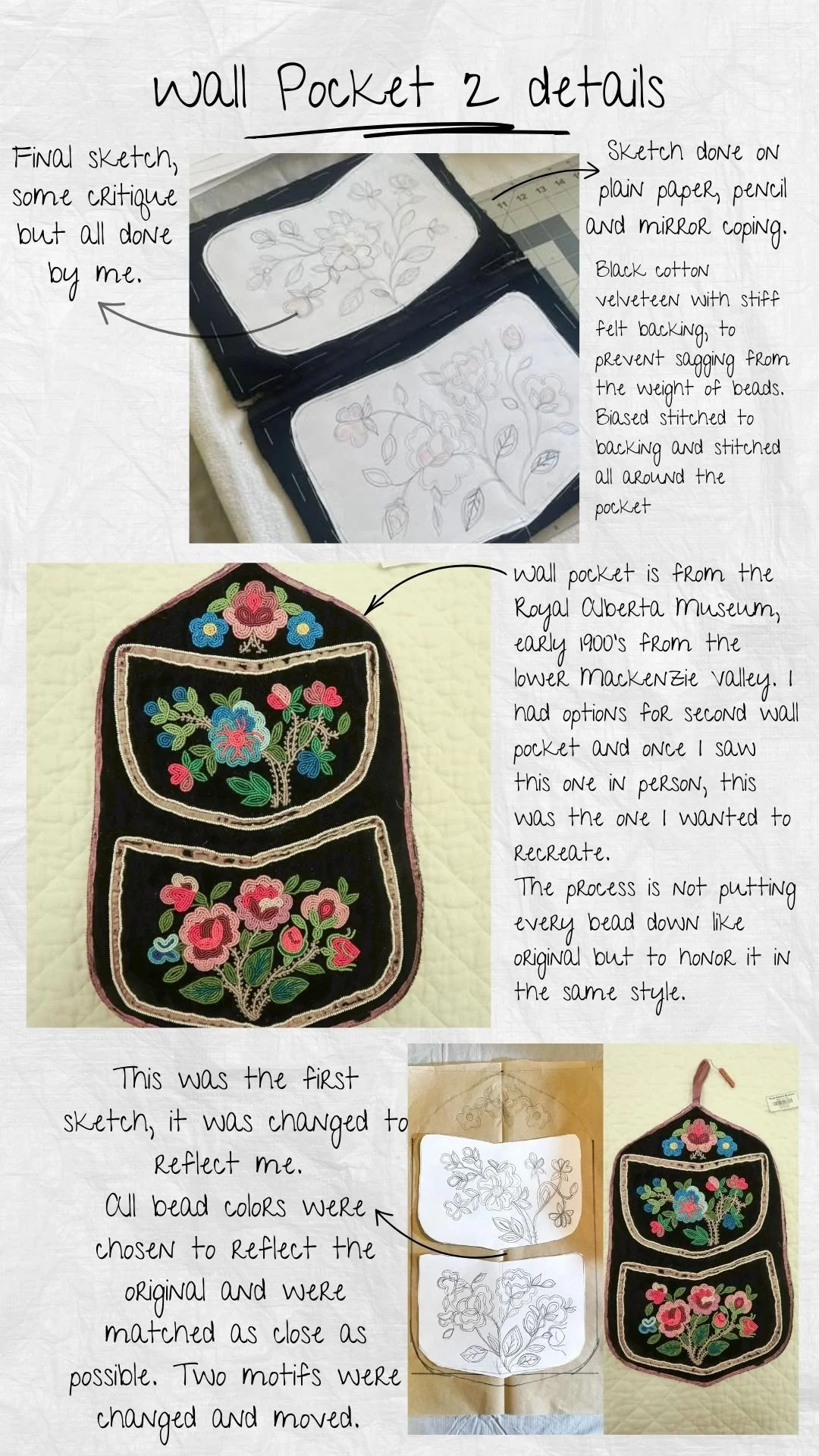

Early March was a Royal Alberta Museum visit to view their Dene Athabaskan Wall Pockets.

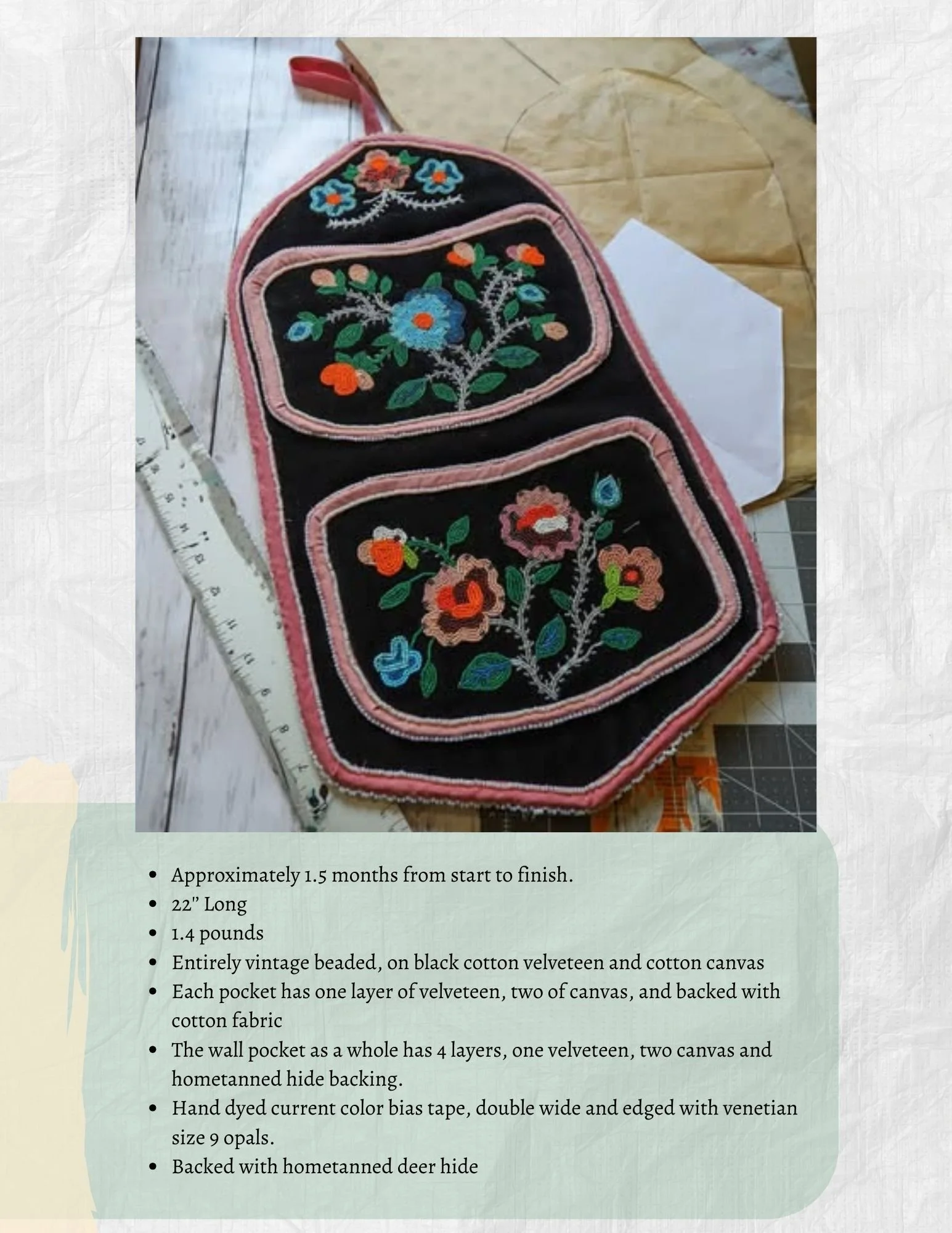

Late March - June was making the 22’’ long wall pocket, with two pockets, hometanned hide backing.

-

I’ll be keeping this up to date, but there will be periods of 1-2 weeks as I work. I’m so excited to share all this and upload all the pics. I’ve watched so many others and their projects, and I loved the updates.

Below is some information on this project. Mahsi Cho to the Alberta Foundation for the Arts for this. This project will take about 6 months using allll the pink Cheyenne beads, and steel cuts.

My current research has been in trade beads and recreating vintage beadwork. With the help and knowledge of mentors, friends and social media contacts, I have been studying and researching into trade routes, our grandmothers work, learning Dene floral motifs and recreating traditional beadwork styles.

We, in the centuries past, have kept our beadwork on everyday items. But in modern times, this has dwindled, kept in museums. As much as possible, we will be using traditional materials from vintage beads, old style Gwich’in florals, beading down on velveteen, hometanned hide. Also, little fact, we used to use a flour and water paste to outline our florals on black velveteen, that you can still see in museums work. While we may not use this technique, the Dene wall pockets will be done as close as possible. This is also in the knowledge that not everything can be replicated or copied, but we will still honor this work as we move it into a modern, contemporary setting.

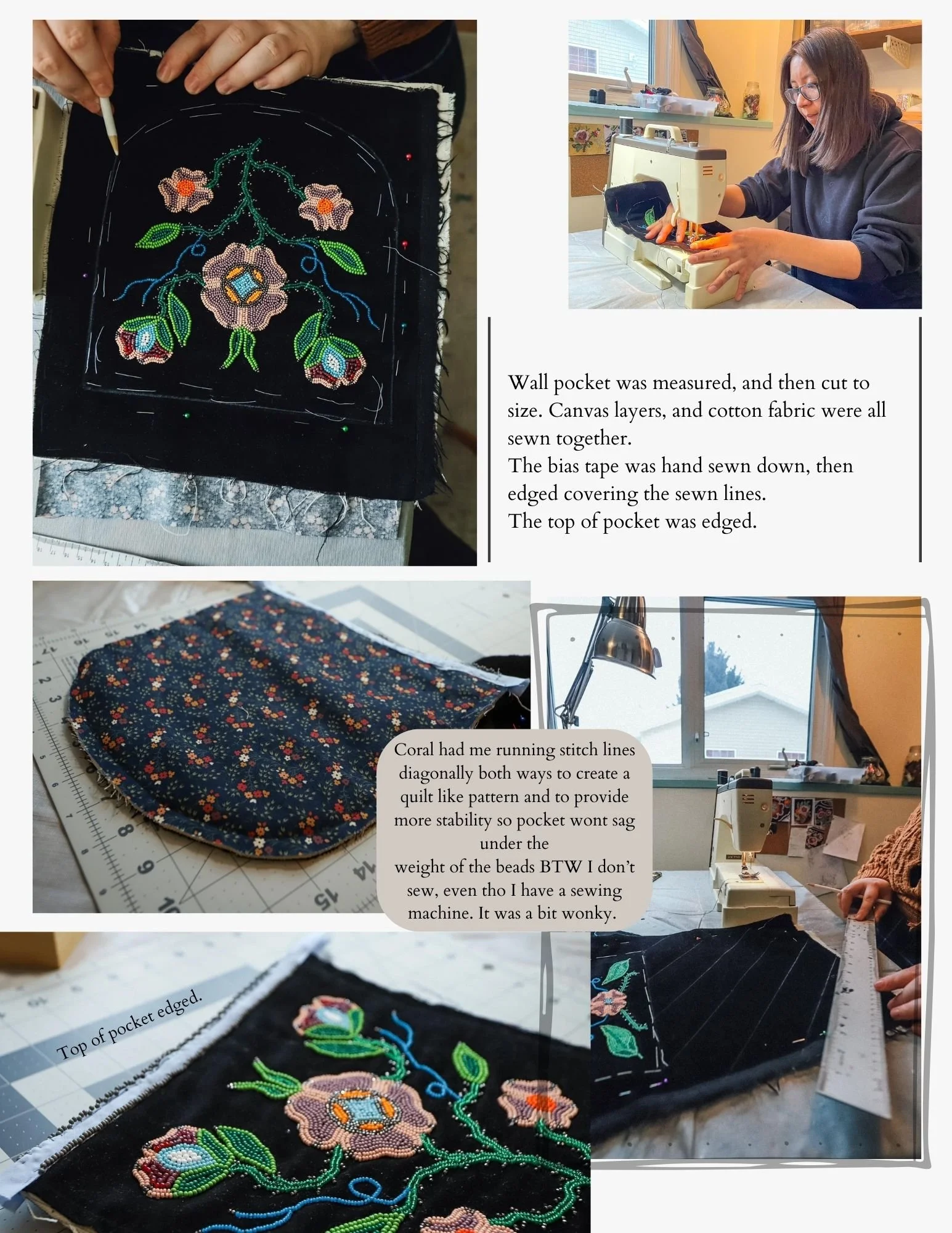

So the grant is providing time for me to look more into motif designs, colors, materials, and beading techniques with a mentor who has knowledge on historical beading methods and materials. In early February, I had my third trip to the Royal Alberta Museum. This time to see and learn more on material finishings for wall pockets. The Indigenous steward, Coral Madge, pulled a dozen wall pockets. These were mostly Gwich’in, but also Cree, Metis and Dene. This was to learn, ask and photograph to see what our ancestors used to finish their wall pockets. Our ancestors used velveteen, trade beads and then I wanted to see how they incorporated this into their work. Some wall pockets were edged in steel cuts, others in plain bias tape. I know that environment plays a significant role in finishing but to see times, places and items was significantly helpful. And let me take five thousand photos.

From the early February Royal Alberta Museum Trip.

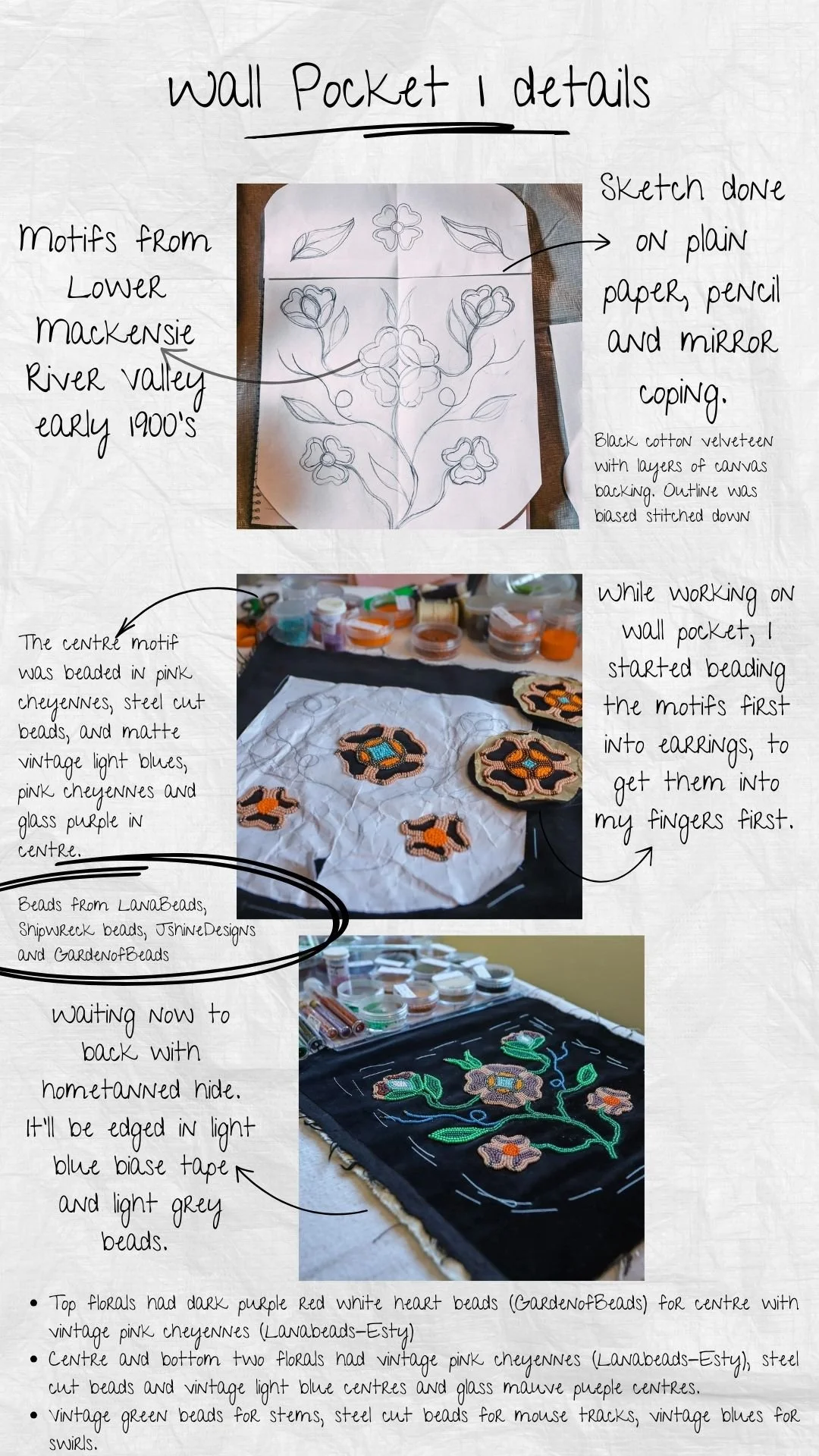

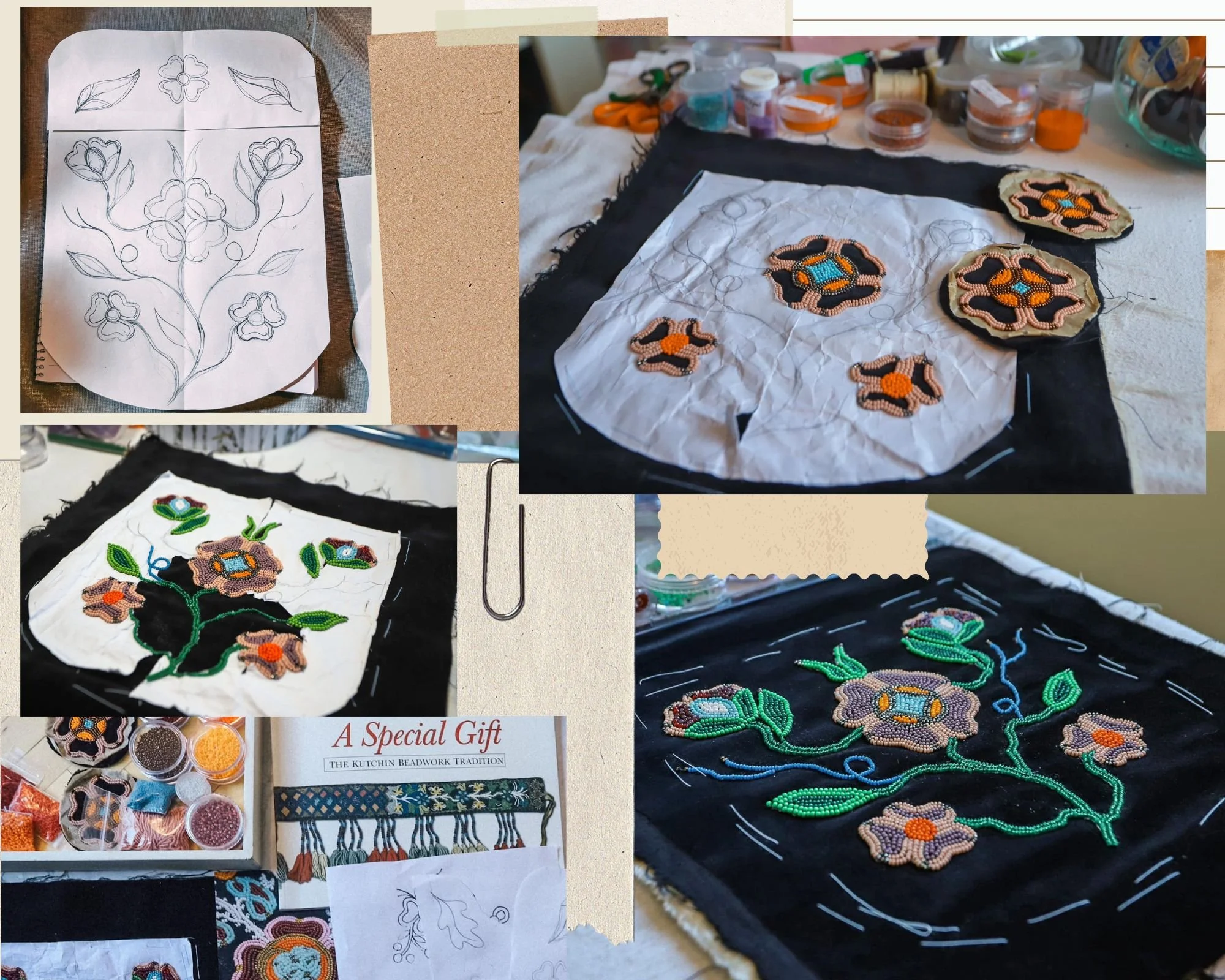

NOTES: A key element of this project was my focused research into early beadwork techniques, motifs, and materials. With the support of Coral Madge at the Royal Alberta Museum, I undertook three visits to study pieces in the Indigenous collections between 2024-25 I examined construction methods, sketching techniques, color palettes, and specific motifs used by Western Gwich’in (Kutchin) women. These included the stylized central motifs common in our region—often symmetrical, minimal, and flowing outward—with stories behind some, like the three-petal “kidney” bean petal, also called ptarmigan foot or dog paw. It’s interesting to note our dependency on animals and that the names are predominantly about animals.

I learned how to translate these traditional motifs into contemporary practice, first sketching them by hand using carbon transfer methods, then stitching them onto velveteen backed with canvas to prevent sagging. The project also challenged me to adapt these larger-scale motifs into smaller wearable forms, resulting in 14 pairs of earrings—far more than the original goal of eight.

Beyond technical development, this work reinforced the importance of cultural preservation through art. I gained a clearer understanding of how materials like velveteen, steel cuts, silk bias tape, and limited color palettes reflected availability and stylistic decisions in the past. I was also reminded how much ancestral knowledge survives in museum collections, waiting to be studied and brought forward into new work. In my readings, I came across this quote.

“As the voices of Indigenous women seldom appear as written in history, Indigenous women's ancestral knowledge(s) as exists in a multiplicity of Indigenous art forms held in museum collections remains unexplored in terms of potential contribution to Indigenous women's ways of knowing. In the orchestration of a decolonizing approach, I seek meaning in historical, cultural and social relationships towards realizing the significance of Indigenous women's cultural production to contemporary Indigenous women's discourses (Suzack, Huhndorf, Perreault, and Barman, 2010).

Goals/Objectives:

This project marked a meaningful step forward in my artistic development by allowing me to focus on traditional Gwich’in beadwork while achieving several core goals: skill building, material knowledge, motif development, and preservation of cultural techniques. With financial support, I was able to access new materials—including vintage trade beads—and dedicate time to in-depth learning, hands-on practice, and creative exploration. Coral guided me in bead shopping, going through the colors, size and using our ancestors work to try and color match.

A primary objective was to develop my skills in sketching and beading traditional floral motifs under the guidance of Coral Madge. Through three visits to the Royal Alberta Museum, I had the opportunity to study archival pieces up close. Coral encouraged me from the start—teaching me how to sketch symmetrical motifs using carbon-transfer techniques and helping me understand how color and shape functioned in historical designs. These hands-on sessions significantly improved my ability design florals with traditional accuracy and contemporary adaptability.

Another goal was to gain deeper material knowledge—particularly around the velveteen, trade beads, canvas, and silk trims used in historical Dene and Gwich’in beadwork. Studying these pieces in-person helped me trace a visual and material timeline. I observed the shift in bead color availability, the impact of environment on design choices, and how women adapted their techniques over time.

The project also met my goal of preserving and documenting skills through journaling and photography. I kept detailed notes on each stage—from motif design and stitching techniques to material selection and final construction. This numbers into hundreds of photos, sketches, and binders full of notes and designs. These records not only supports my own learning but will serve as reference material for future projects, workshops, and knowledge-sharing with other artists.

Professionally, this project has expanded my portfolio, enriched my process, and helped position me more confidently as a Gwich’in beadwork artist committed to cultural continuity. It also laid the groundwork for future projects, public presentations, and potential exhibitions rooted in traditional knowledge and practice. I look forward to moving this into my community.

And Mahsi Cho, thank you for all your support, comments, pictures sent and all the conversations. Mahsi! I loved every part of this.